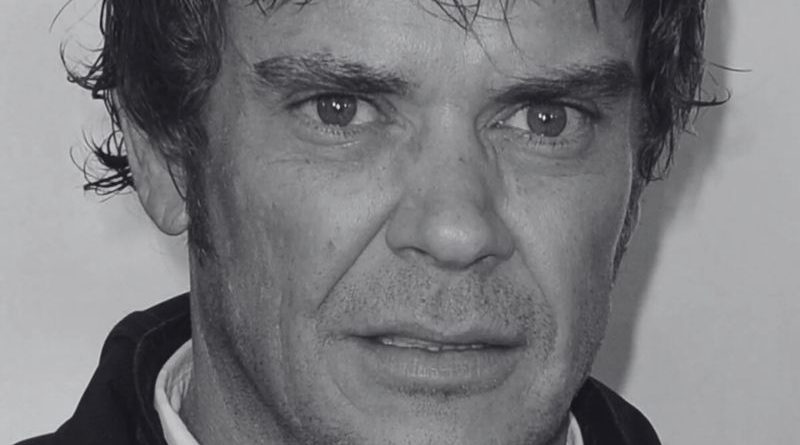

Brandon Auret on Why South African Film Needs “Businessmen”, Not Just Filmmakers

From the gritty slums of District 9 to the galactic battlefields of Zack Snyder’s Rebel Moon, Brandon Auret has established himself as a versatile and commanding presence in modern genre cinema. Auret has a rare, dual perspective: having experienced the Hollywood system as an international actor and as a co-owner of A Breed Apart Pictures, where he’s faced the challenges of domestic funding. Going beyond the art of performance, this conversation confronts the business of survival and the structural changes needed to secure the future of South African cinema.

I watched your recent video on LinkedIn talking about the new initiative, and I wanted to know if you can share the story behind this…

I read Richard Branson’s book, ‘Just Do It’, and he said something in there that made me think about show business differently. It’s a business that relies on connections… but at the end of the day, it’s all resolved by investors and businessmen. You need to make sure that the businessman understands the show part because the show doesn’t understand the business… So you’ve got to bring them together.

I got into conversation with a woman named Carrie, who owns a company called Gemini. It’s a bonding company… and just started chatting to her about the business and how the business works and how it really, really works.

She got involved with some people… [and] we’re basically doing a fundraiser, and it’s going to be a year-long fundraiser. We’ve been told that if we hit whatever mark… they’ll double it. Which has given us a lot of hope because that’ll give us enough money to get our slate going.

How is the fund structured regarding ownership?

Then we will get a script supervision department, we’ll get production teams, production accountants… so there’s no money disappearing into this stuff. We will sponsor the film… and maybe we can give you like 50% of the film, 75% of the film, but we want to get 100% of the film if we can… and then we don’t own that film, we own a percentage of that film for the rest of the life of that film, after that money has been paid back, but you own the rights. So if your movie does really, really well… we want just a percentage of that, and then the money goes back into the fund, and then repeats, and repeats.

So how does it work, is it something that you’re designing so that people will come to you with ideas to get funding?

100% dude. And we’ve already got investors involved. Let’s say we get a really, really good script… and it gets a distribution deal… and we’ve sold your script for $200,000 to $1.8 million.

We’re going to take our cut, and then this is what you will be able to claim over the various stages… If you get that paper first, you get that guarantee signed off, we’ll give you the money up front, and we’ll take the hits on that, but then we want a percentage.

Where do you think government’s funding initiatives have failed?

I can’t answer that because I don’t know where they’ve failed. Why isn’t it working? Because I think they’ve been taking advantage of it. And I think money has been stolen. I get emails and emails of people telling me… “I need to prove to them that I’ve got money in my account.”

What is your stance on executive fees in funding?

I made a promise to my team… I said, this thing of taking 10% off the top… what a load of sh*t that is. 10% of my budget? So, you’re telling me that if I get a R36 million movie, you are going to just get R3.6 million and say thanks very much? That should go back into the film. Straight back into the film. That’s another day with stunts. That’s another week’s worth of shooting. If a film makes money. Then, game on, brother. That’s where we as executives are going to make our money. If there’s a nice hard waterfall afterwards.

You mentioned issues with “target markets” regarding funding…

I get that a lot from certain areas in our industry. Where it’s like, “your films are great but they’re not our target audience.” What is your target audience? “Black middle class. Rich black middle class.” You don’t think they’re going to enjoy this film? Because if I watch all of the films that have been made for your black middle class people, they’re English speaking films. So I can only draw one conclusion from that. Okay, cool. Wrong skin colour. No problem. I’ll go do it on my own.

What is the economic reality of the current grants?

We are trying to make films on next to nothing. R1.8 million budget because that’s all the DTIC is giving. R1.8 million for a film? Come on, dude, that’s nothing. I mean, KZN is offering that… We’ll come up with 1.2, 1.3, 1.4. Just as a, whether it’s pre-script or pre-production, that R1.8 or R1.3 or R1.4 million does a lot for a film. But it’s not going to finish the film.

What is the potential impact of film funding on the local economy?

There’s a theory… that for every Rand spent in a town or at a place or in a location, it’s times by four. Because it would go to paying the person who’s being paid, the family members, the shopkeepers. Now everybody’s suddenly got a little bit of extra money.

Just how big is our industry?

There are thousands. 16,000, 17,000 people in our industry. And the industry in this country brings in about R1.8 billion… into a country. A small little South Africa.

What would you say is an area where our weakness is as a film industry?

Distribution. And the problem is what’s going to happen in the future is films are going to start self-distributing. Because instead of distributors… helping those films make money, I’ve heard stories where the film is in so many different places and the filmmakers are still waiting for their money.

You mentioned vertical films and passive income…

We’re offering everyone shares. So as long as that little thing, that episode that you’re making, if that thing is making money, there will be dividends for you. It’s your passive income.