Three Films That Are Just Conversations

Three of the best films that are all dialogue, and as little plot as possible.

The Before Trilogy

To keep from spoiling the subsequent films in the series, each released about 10 years after the last, we’ll focus on only the first film; Before Sunrise. Like very few films before or since, Before Sunrise captures the delicate blossoming of romance between young people. Over the course of a single evening and night in Vienna, the film follows Jesse (an American catching a flight home in the morning) and Céline (a student returning to study in Paris).

He is a little cynical and uninhibited. She is a little idealistic and wistful. Their conversations, so spontaneous and natural and yet so mesmerizing, reflect each partner back at the other; in discussions and disagreements, the full picture of their potential fulfillment in one another dawns on them, slowly. Their pretense for taking the time to get to know each other is that, this way, neither will have to wonder if the foreigner they once saw on the train might’ve been “the one”. That if they talk for a little while longer, they’ll realise the unremarkable truth of each other.

This does not happen. They talk and talk and talk and grow closer and closer and closer. What do they talk about? The same things you do; family, feminism, breakups, money, greatness, caring, God, the works. The moment the chemistry between Jesse and Céline becomes unbearable is one of the rare scenes where they don’t speak at all, but never underestimate the importance of body language. Early on in their escapade, they cram into a small listening booth at a vinyl record store and ‘listen’ to a love song. The close quarters and romantic ballad make them a little nervous, as they telegraph the ambiguity of their relationship, and the two glance back and forth, at and away from each other, making sure the other doesn’t see them looking. “I believe if there’s any kind of God it wouldn’t be in any of us, not you or me but just this little space in between. If there’s any kind of magic in this world it must be in the attempt of understanding someone, sharing something.”

Certified Copy

From the spark of new love to the tension and steady strains of middle age. A British writer gives a lecture in Tuscany on his new book. He posits that any arguments for the authenticity of a work of art over its copies are irrelevant, since all art is a copy of its subject, and the copies are themselves originals of their own. Certified Copies.

A woman in attendance asks to meet him, and the two go about making their way around the nearest village. They seem to be strangers, though their relationship could be ambiguous, and it seems past a certain point to have changed completely, in a very literal sense. They begin to act like a fraught married couple. Which relationship was authentic, and which a copy? Does it matter, when the emotional distance of the man and desperation of the woman stay the same? The film’s reproduction of this relationship rings true to life in its constant vacillation between the hopes and disappointments, wit and urgency, connections and misunderstandings, admirations and resentments of each day.

Characters speak directly into the lens of the camera, partly to garner the same intimacy Ozu produced with this technique, and partly to confront the viewer with these ideas, and these people, directly. The emotional truth of the ‘couple’s’ dialogue is helpfully enriched by their skill as conversationalists, and director Abbas Kiarostami’s eye for beautiful compositions ensures that we are not only following the characters, but viewing them in ever-shifting contexts. “Look at you wife, who has made herself pretty for you. Look. Open your eyes.”

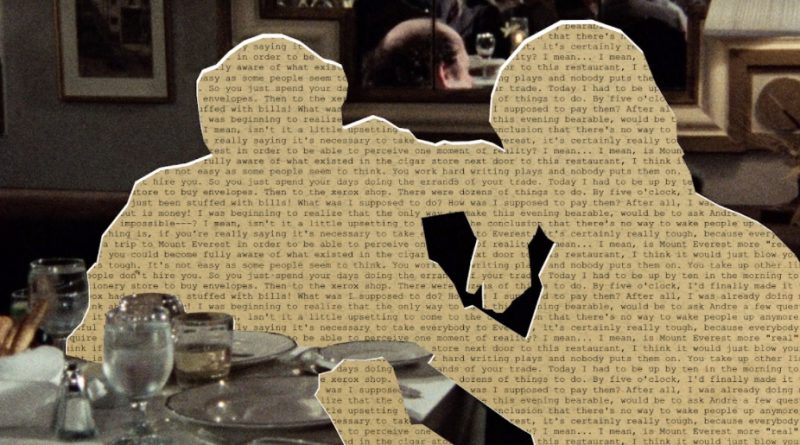

My Dinner With Andre

You could argue that the previous two films cheat their way to audience involvement by parading so lofty an aim as romance, that the conversations do not stand on their own because they are in service of resolving their characters’ emotional desires. We turn then, to the crown jewel of chatty cinema: My Dinner With Andre.

Wally, a homebody actor and playwright, arrives at the Café des Artistes to meet Andre for dinner. Andre is a theatre director who has, in the ten years since the pair last saw each other, travelled the world in search of enlightenment. He begins to recount his pursuits, and Wally weighs in pragmatically. Who’s wasted the last ten years? With Wally and Andre not having much of a bond, even before the latter’s extended dalliance with adventure, the film relies entirely on the tension between their worldviews, and more importantly, the substantive and thought-provoking talking points they race past and dwell on in equal measure. It is a uniquely spellbinding film, and the fact that two people talking, probably the cheapest film you could make, isn’t a more populous genre, speaks volumes to the small miracle it must be to pull one off.

“And when I was at Findhorn I met this extraordinary English tree expert who had devoted himself to saving trees… He said to me, ‘Where are you from?’ And I said, ‘New York.’ And he said, ‘Ah, New York, yes, that’s a very interesting place. Do you know a lot of New Yorkers who keep talking about the fact that they want to leave, but never do?’ And I said, ‘Oh, yes.’ And he said, ‘Why do you think they don’t leave?’ And I gave him different banal theories. And he said, ‘Oh, I don’t think it’s that way at all.’ He said, ‘…they’ve built their own prison—and so they exist in a state of schizophrenia where they are both guards and prisoners. And as a result they no longer have—having been lobotomized—the capacity to leave the prison they’ve made or even to see it as a prison.’ And then he went into his pocket, and he took out a seed for a tree, and he said, ‘This is a pine tree.’ And he put it in my hand. And he said, ‘Escape before it’s too late’.”

For some viewers, these long stretches of conversation and only conversation may fly in the face of what a movie is supposed to accomplish. If it’s conversation you want, why not just have one of your own? There are two answers: most discussions have perfunctory pauses and pleasantries; they stink of the social lubricant we have to apply to get to the good stuff about an hour in. There’s no guarantee the conversation won’t exhaust rather than stimulate you. Secondly; landing on a talk that is both enveloping and existential in scope is like approaching a small bird; on occasion it might come to you, but if you go looking for one you’ll scare it off. These films, and these people, wait patiently to be watched again; to catch up for old times’ sake.